Menu

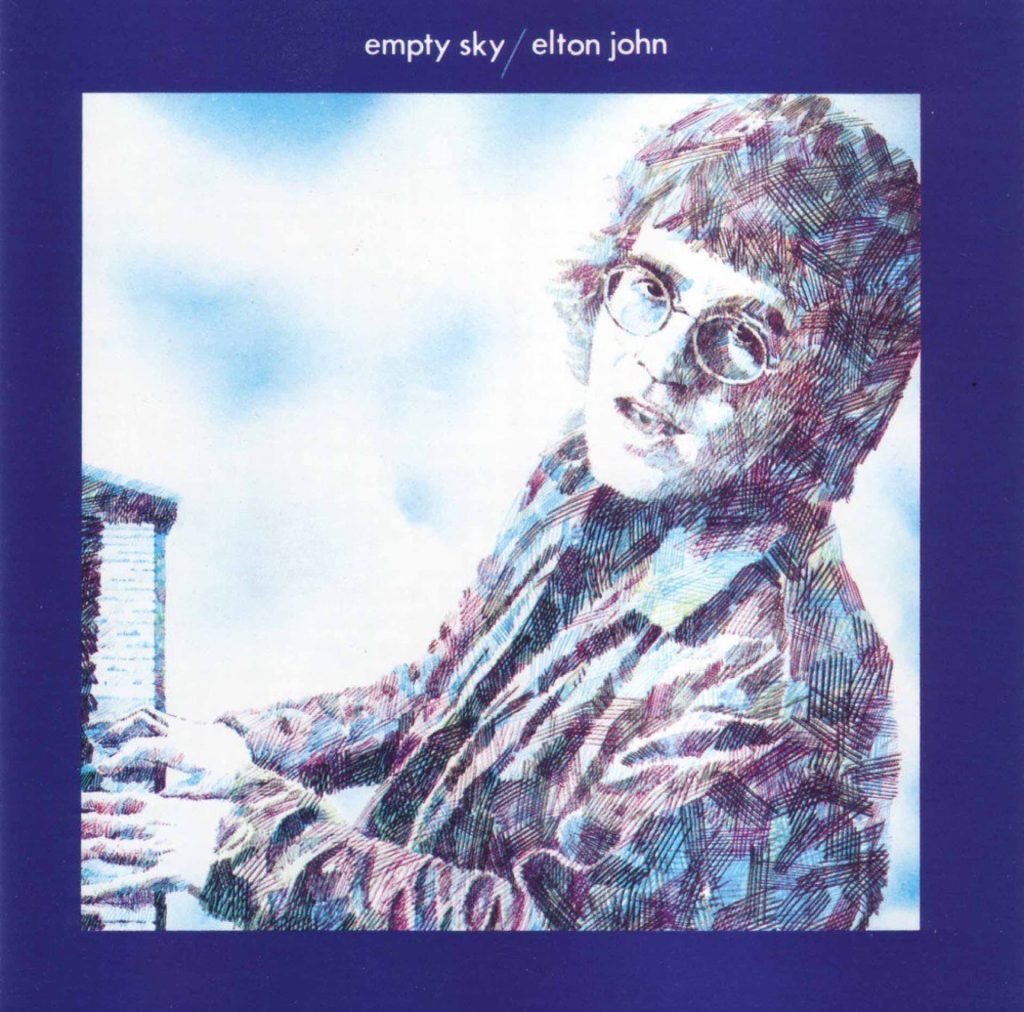

‘Empty Sky’ – Elton’s First Album Turns 50 today

But our Empty Sky was filled with laughter.

When lyricist Bernie Taupin wrote those words in the Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy song, We All Fall In Love Sometimes, it was a mere five years after the release of Elton’s debut album to which it refers. But, oh, those five years…

Empty Sky is often too easily assessed with a heavy dose of hindsight. After all, what Elton and Bernie accomplished in the succeeding half-decade could not help but overshadow the 1969 album and earlier efforts, three stand-alone singles, none of which charted.

By John F. Higgins

Yes, the cultural echo of the 1969 LP has perhaps been reduced to a note or two in the Elton John vs. Pnau #1 album, Good Morning To The Night (2012), and a fleeting glimpse of the back cover in a particularly heartbreaking scene in the recently-released movie ROCKETMAN.

However, today, in honour of its 50th anniversary, we joyfully dive deep into Empty Sky – the album that started it all.

‘Oh, Bernie’s got some new lyrics? When can we get in the studio??’ We were like kids in a candy store.

Writing and Recording

The sessions for Empty Sky ran from November 1968 to the end of January 1969 at Dick James Studios at 71-75 New Oxford Street, a stately building situated at the top of London’s Soho area. Elton and Bernie had been toiling within its walls since mid-1967, trying to give publisher Dick James the “commercial” tunes he had hired them to write for his roster of artists.

As guitarist Caleb Quaye explains, “Dick James was old-school but the pressure of him wanting something for Englebert Humperdinck or Lulu or whatever, I don’t think that should be seen as a negative. Dick was like a father to us. He gave us the opportunity to learn our craft in that little studio. And that’s what we did. We couldn’t wait to get into the studio to do our demos or whatever. We couldn’t wait to work this stuff out!”

With the arrival in 1968 of song-plugger Steve Brown, things began to shift for the pair. Once the “elder” mentor (he was a year older than Elton, whom everyone still called “Reg”) listened to their output to date, he had one suggestion, “Stop writing for others…write for yourself.”

“Steve was essential to the journey,” says Caleb in a conversation for this article. “Especially when you look at this particular period of development. All of that stuff for Dick James was, ‘Well, let’s try this.’ It was trying to form something. ‘We’re not quite sure where we’re going but we’ll just go this way because it feels good. When we get there, we’ll know it.’ Skyline Pigeon was, for them as a pianist and lyricist, probably the first time when the search was over.”

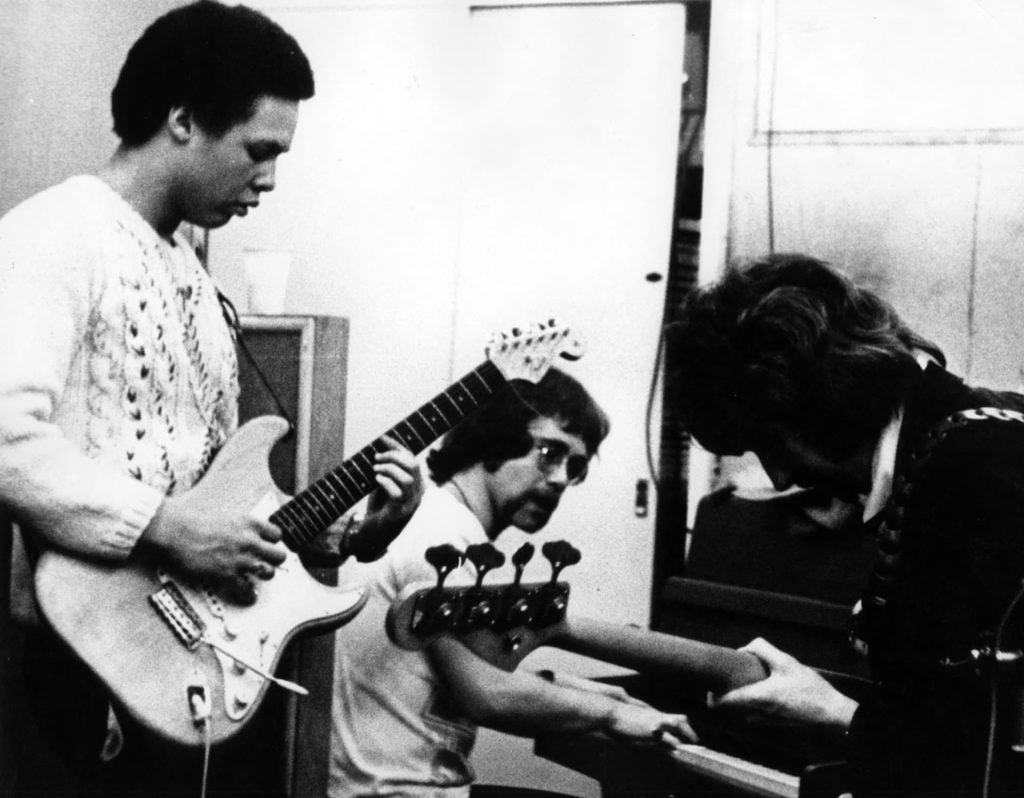

Elton at DJM Studios, with Caleb Quaye and Tony Murray

On October 28, 1968, Elton performed Skyline Pigeon at BBC Radio’s Aeolian Hall for the Stuart Henry Show. A couple of months earlier, the song had been covered on singles by Roger James Cooke and Guy Darrell. This gave Elton and Bernie the encouragement they needed to continue heeding Steve Brown’s advice.

Elton appeared on BBC Radio again (this time at their Maida Vale Studio 4 for John Peel’s Night Ride programme) on November 27, 1968, introducing solo versions of three more songs that would appear on Empty Sky: Val-Hala, Lady What’s Tomorrow? and The Scaffold. The songs were adding up, and by the time the first week of the new year was over, Elton had written his title track. By now, Elton was at the Dick James studio four-track recording board with Caleb, drummer Roger Pope, bassist Tony Murray (from Dick James Music stable-mate Plastic Penny), and others, with Steve Brown producing.

“It was a natural progression,” Caleb explains. “Steve had produced the Lady Samantha single, which Hookfoot [Caleb’s band with drummer Roger Pope] was on. At that time, Elton didn’t have a band. He would work some of his songs out at Hookfoot gigs. This was before the trio [with Nigel Olsson and Dee Murray]. So we were it. It got to the point where Steve thought we should do an actual album. And that was very exciting!

“We were all playing live together in the studio – a lot of looking at one another and head-nods and everything. There was no glass window to the control room; the producer could see us via a [black-and-white] TV monitor hooked up to a camera in the studio, but we couldn’t see into the control room. We wouldn’t know to stop playing [if there was an issue] until they hit the talk-back button and told us to hold on.”

Musicians

ELTON JOHN: Upright acoustic piano, Hohner Pianet electric piano, organ, harpsichord, vocals (double-track and harmony vocals on some songs)

CALEB QUAYE: Conga drums, electric guitars (1964 Fender Stratocaster), acoustic guitars (1964 Gibson J-45)

ROGER POPE: Drums, percussion (tambourine)

TONY MURRAY: Bass guitar

DON FAY: Flute (on 4 songs), tenor saxophone (on Hay Chewed)

GRAHAM VICKERY: Harmonica (on Empty Sky)

CLIVE FRANKS: Whistling (on Hymn 2000)

Illustration by David Larkham, taken from the 1969 promotional material used for 'Empty Sky'.

It's difficult to explain the amazement we felt as the album began to take shape, but I remember when we finished work on the title track... it just floored me. I thought it was the best thing I'd ever heard in my life.

Track-by-Track

Empty Sky

Written January 7, 1969 at Elton’s home in Pinner.

Recorded January 14: take 6

Elton proudly included this song on his “My Life in 20 Songs” article with Cameron Crowe for Rolling Stone. “A great rock & roll track. I love it to death. I remember doing the vocal in the stairwell to get that echo, in a very small studio in London. [Caleb Quaye’s] guitar solo was done in the stairwell as well. It came together so brilliantly and still sounds so good. It’s hard for a piano player to write a rock & roll song. It sounded like a Stones song. I thought, ‘I can do this.’”

The Rolling Stones influence on that song was intentional, referencing the recently-released Sympathy For The Devil, which everyone was intently listening to at the time.

The song opens with a conga drum and piano intro. Caleb recalls, “I played the congas on the basic track [throughout the song], and then put all the guitars on afterwards. What made it easy was working with Roger Pope. Roger and I were very, very tight, musically. We spent a lot of time playing together. And his time-keeping was so perfect. So, when he laid down a track – you have to kind of think ahead – I knew exactly where to put my stuff in context with his playing. It was a lot of fun.

“The solo was mostly board effects. Back in 1969, we had nothing. I had a wah-wah pedal and a volume pedal, a combination all-in-one, and that was about it. So, any distortion was coming from cranking the amp a little bit. There were no reverb or delay pedals or anything like that. Very organic.”

Val-Hala

Recorded January 28: take 9

The basic track has Elton on (a rented) harpsichord, Caleb on acoustic guitar, and Roger and Tony. Elton later overdubbed piano, electric piano and organ. At song’s end, Steve Brown employs the unusual effect of fading down the band whilst leaving the harpsichord at normal volume for a while longer.

Caleb: “My acoustic guitar was very easy to record; engineers loved it. It was microphone-friendly, with that old wood. It had a great low and mid – very warm but crisp in the highs. It just would sit very well in a track.”

Western Ford Gateway

Recorded January 28: take 7

A song written for the album, with hints of Procol Harum in the lyric. Caleb remembers being asked to create the opening guitar lick, “[Elton would] have the song laid out on the piano and he’d play it down with just a chord sequence for the intro. Or he may use the first four measures of the chorus or something to start it off. And [Elton and Steve] would say, “Could you come up with some guitar thing for the intro?” So I’d come up with it. Necessity is the mother of invention, as they say. And on Western Ford Gateway, I put down one guitar lick for the intro; everybody loved it and Steve said, “Oh! Do you think you could put a harmony line on that?” [laughing] “Okay, sure…no problem!”

Hymn 2000

Recorded January 22: take 12

The first verse to this song was recited (sans music) by Bernie on a Dick Clark television special in the mid-1970s, as an example of one of his more esoteric bits of lyric-writing.

There are no drums on this track, just Roger Pope keeping the beat on tambourine. “Musically,” Caleb notes, “with the fact that there’s no drums and the way he’s singing the melody and that groove that kind of lopes along…that’s Joni Mitchell. We loved Joni Mitchell.”

Lady, What’s Tomorrow?

Recorded November 19, 1968: take 4

The first appearance on an Elton John recording by long-time and current drummer Nigel Olsson, who was a session player at the studio and was also in the band Plastic Penny.

The interplay between Elton’s piano and Caleb’s acoustic guitar set the template for later songs such as First Episode At Hienton and Where To Now St. Peter?. “As a guitar player I’ve always preferred playing with a keyboard player,” Caleb says. “Because the tonal palette is wider. If it’s all guitars, you’re all in the same space, so to speak. Whereas with keyboards, there’s a lot more options – a lot more colors. I think that was a major part of our musical chemistry. We just worked so well together. Elton and I made it sound so full with our interplay: my finger-picking along with his arpeggiated piano work. It just worked beautifully.”

Sails

A favourite amongst those who worked on the album, this song was later performed by Elton with Hookfoot on July 11 at Aeolian Hall for BBC Radio’s Symonds on Sunday. The original lyric includes lines that were omitted from the recording, and, interestingly, does not contain the phrase, “And together we just watched the sails.”

Caleb: “It’s a track that I think is ahead of its time. Compositionally, it’s Steely Dan before there was a Steely Dan; listen to the chord changes. It absolutely stands the test of time.

“All of that guitar work was done live [on the take] – the solo, everything. I just pulled the solo from out of the air. The harmonics at the beginning is my volume pedal – just a swell effect – and the solo in the middle of the song would have been the wah-wah pedal.”

Elton and Hookfoot performed this song, along with Empty Sky, on July 28, 1969 at BBC Radio’s Camden Theatre for the Johnnie Walker Show.

The Scaffold

This song is a hybrid of The Band’s 1968 song Long Black Veil, which includes the line “The scaffold was high…”, and Elton and Bernie’s most-cherished folk artists of the time: Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and David Ackles, who would be Elton’s opening act for his US debut performances 19 months later and for whom Bernie would produce the album American Gothic in 1972.

Elton’s use of his own harmony vocals in the choruses of this song is about as close as this album gets to background vocals. In fact, Empty Sky is the only studio album in the entire Elton catalogue that has no backing singers.

‘Skyline Pigeon’, was the first good song that Bernie and I wrote.

Skyline Pigeon

Elton is the only musician on this track, singing and playing harpsichord as well as overdubbed organ. He has often told the story of how the vocals were recorded out on the fire escape of the Dick James building, to get the specific metallic echo effect Steve Brown was looking for.

Of all the songs on the album, Elton has performed Skyline Pigeon in concert the most, spanning from 1971 to 2017. It was re-recorded in 1972 with Elton on piano with his band and an orchestral arrangement by Paul Buckmaster.

Gulliver/Hay Chewed/Reprise

Gulliver’s lyric tells the tale of one of Bernie’s childhood farm dogs passing on.

Caleb describes his work on the sessions: “That echo at the beginning was a board effect that the engineer would give back to me in my headphones while I was playing. In the verses, that’s me just applying some of my Hendrix licks to what Elton was doing. That’s The Wind Cries Mary.”

At around the 3-minute mark, things shift considerably into an instrumental called (in a pun from the recent Beatles hit Hey Jude) Hay Chewed… sometimes written as “It’s Hay Chewed.”

Caleb says, “I honestly can’t remember whose idea this was. I think it was Elton’s idea, the ‘jazz combo’ thing, or Elton and Steve’s, to do sort of eight measures in one style and then another eight measures in another, and so on. Count it off and ‘here we go.’ I grew up with jazz and Roger also was a jazz player, too. He was a very versatile drummer. His dad was a jazz drummer and he grew up listening to that. So, we used to play jazzy stuff and bluesy stuff.”

Finally, in what is perhaps the most dated decision on the album, Steve Brown chose to include brief snippets of each song for the tag known as Reprise.

Legacy

Empty Sky was released on the fledgling DJM label on 6th June, 1969 (it would not come out in the US until 1975) and while it did not make it on to the UK Album Charts, it received favourable reviews and was spun on the British radio turntables enough to inspire Dick James to fund a subsequent album, 1970’s Elton John.

“Everybody was happy with Empty Sky,” explains Caleb. “We loved it. It was a lot of fun. Bear in mind we were still young at the time. We were still in the process of learning our craft. On the way, but not yet fully-formed. Within the next couple of years, it would come together, of course.”