Menu

Paul Buckmaster: In His Own Words

It is impossible to overstate the impact and influence that arranger Paul Buckmaster had on Elton’s career and early albums.

By John F. Higgins

Paul, who passed away on November 7, worked as Arranger on all or parts of eight Elton studio albums between 1970 and 2001 as well as the Original Motion Picture Soundtrack for Friends, for which he is also credited as composer on five songs. In addition, Paul’s work can be heard on six non-LP B-sides to Elton singles in the 1970s and 1980. In total, Paul arranged 52 songs for Elton – playing on two others he did not orchestrate – some of which are the artist’s most identifiable.

Born in London, England on June 13, 1946, to an actor father and concert pianist mother, Paul attended the Naples Conservatory in Italy on a cello scholarship at the age of 11. Five years later he won a cello scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music where he met future Elton percussionist Ray Cooper, who was also a student there. Elton himself attended the Academy during part of this same period.

Since his passing, Paul has been feted by Elton (“Farewell Paul Buckmaster. So heartbroken. He helped make me the artist I am today. A revolutionary arranger who took my songs and made them soar. Irreplaceable.”), keyboardist Kim Bullard, Ben Folds, Axl Rose and others with whom he worked over the years. His arrangements can also be heard on songs by the Grateful Dead, the Rolling Stones, Carly Simon, Harry Nilsson, Stevie Nicks, and Train, amongst many other artists.

Today we are honouring Paul with his own comments on his start and some of his subsequent work with Elton, taken from interviews and public appearances Paul made during the 1990s.

On getting his start as an arranger

“There is an honorable and long precedence going back to the early rock and roll records that had strings on them. Not in the style I wrote; they were generally one line pitched in a relatively high register so they would seem separated from the rest of the frequency spectrum. Usually, a small violin section playing little tweedly-bits.

“And then of course as we go along into the ’60s we have George Martin establishing incredible new ways of doing it with the Beatles. Both with the classical timbre, which was things like Eleanor Rigby and Yesterday, and outrageous examples like I Am The Walrus, which has this insane string arrangement, and Within You Without You, which was this wonderful Indian-style arrangement. And then I showed up and just sort of made it up as I went along.

“I started as an arranger with no experience and I just had to learn on the job. I never trained for it and all of a sudden I was writing pop arrangements for small string sections…a little brass, percussion, or whatever. But never symphonic. When I started working with Elton, his style is so based on a kind of classical theme – with (ranging from overtones to full-blown) gospel/R&B and of course his fast rock, kind of honky-tonk, style. But so much of that first album was very classically oriented. His writing and piano accompaniment. So that just naturally dictated what I did.”

On meeting Elton

Paul first came to Elton’s awareness via David Bowie’s 1969 hit song, Space Oddity, which was one of Paul’s first arrangements. At the time, Elton and his manager Steve Brown were looking for someone to produce and arrange the follow-up to Empty Sky. Steve had produced that effort and felt that Elton needed someone else behind the board to take his career to the next level. They also determined that the duties of orchestral arranger and producer be separate, which precluded them from sealing a deal with Beatles producer George Martin, whom they approached but had insisted he be allowed to handle both duties. Steve and Elton both loved Bowie’s record, so an introductory meeting was set up with Paul during the dinner interval of a Miles Davis Quintet gig – Paul and Miles were becoming friends and would soon be collaborators – at Ronnie Scott’s nightclub in London on November 2, 1969.

“Steve Brown introduced me to a quiet young man, Elton John. Steve asked me if I would be interested in listening to some of his demos, to which I replied, yes.”

The next day, Paul was messengered a tape of some of Elton’s demos and when he heard the contents (Your Song, Sixty Years On and Take Me To The Pilot) he knew he had found his next muse.

“It only took the first hearing for me to call Steve and express my enthusiasm. I heard the potential of what l was going to write. I had already begun to hear what I was going to write on Your Song, for a start. It was the sort of thing that I was dying to have a go at, in that context. Give me a song like that and that’s what I wanted to do with it. In fact, as I received each song I got more and more excited because I could hear what I was going to do.”

Steve and Elton asked Paul if he could recommend a producer to helm the album. Paul suggested Gus Dudgeon, with whom he had worked on Space Oddity.

“I then called Gus, took the tube to his office and played him the demos; it took about a minute of cajoling to persuade him that were we to work together on an Elton John album, it would be sure to be a big success — that’s how sure I was of how great it was going to sound.”

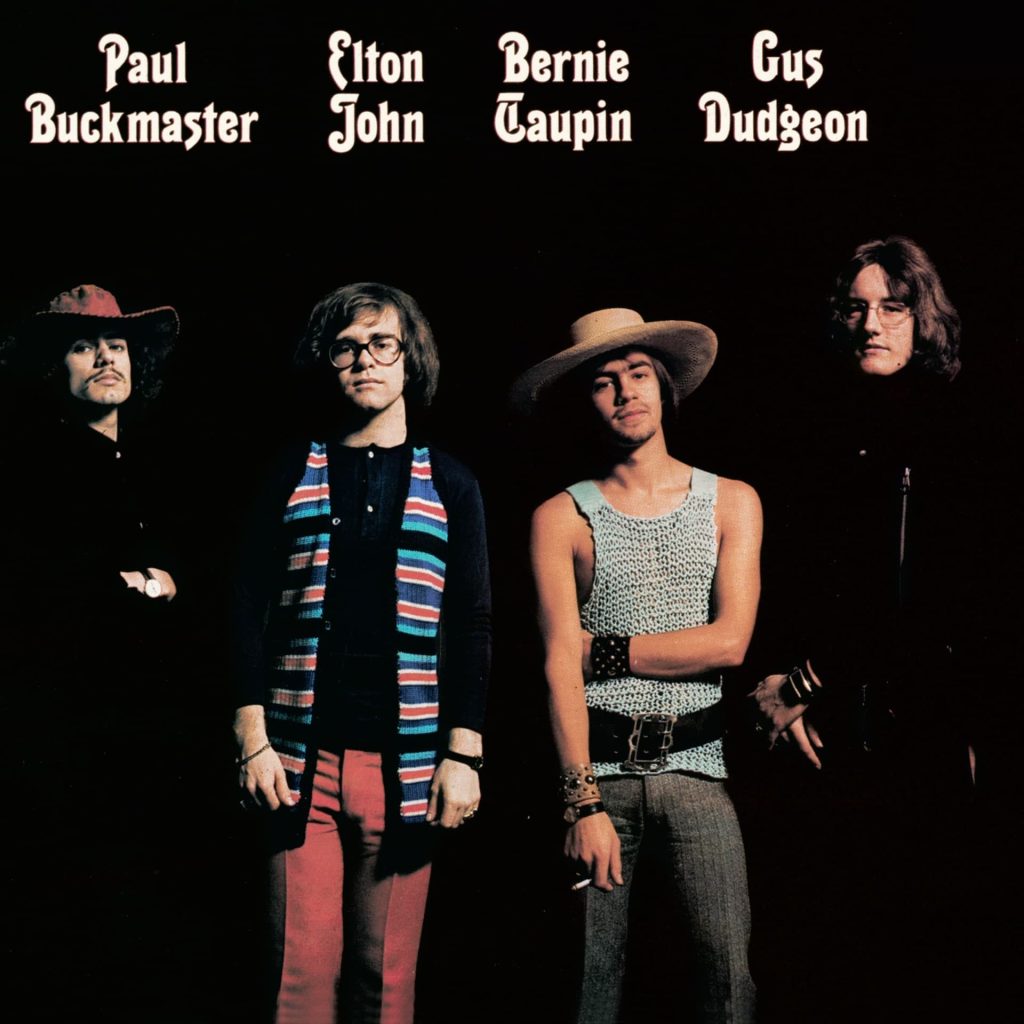

Rear cover of the 'Elton John' album (1970) showing Elton and Bernie with the late Paul Buckmaster and Gus Dudgeon.

The ‘Elton John’ album

Elton’s second album was recorded and mixed in 12 days at Trident Studios in the SoHo section of London during the winter of 1969-70. Before the sessions began, Paul and Gus sat down and discussed the arrangements to each song.

“Gus and I would meet in his office and sit at his table, listen to the demos, follow the songs on the lyric sheet and make notes next to the relevant lines. We went through every song, possibly, in two sessions in his office. We would discuss where we would like the first string entry, if that was the case. Say it was a song where the piano started, for example, Your Song. We would say, ‘Okay, we will start with strings in the first verse. We won’t bring the drums in until the second verse.’ Stuff like that. After having done the routining (that’s what this process is called), I would take the notes home with me and start scoring and let my imagination have full rein.

“As a matter of policy Elton decided to not be involved in the creative decisions that Gus and I made. Elton literally said, ‘I don’t want to be involved in this. I trust you guys.’ He was wonderful. It’s not often that you have an artist do that. He had so much trust that he allowed us to do what we felt was right for each song. Each song was its own mini-film that had its own cast. We treated each song as an individual entity in itself.

“During the recording dates we were all amazed at what I did, me included. In a short time I can’t possibly convey to you the atmosphere of the studio every time we heard an arrangement for the first time. Everybody was going, ‘Wow!’ and just freaking out. I had heard it in my head, of course, as I was writing it, but to actually hear it for real being played by instruments, coming back at me from an orchestra, is an experience that remains with me years later.

“The piano always went down with the first elements, that is, with the rhythm section (if there was one). Everything else would be added to that. In some cases we might record brass and woodwinds together with the rhythm section and then overdub the strings. Actually, we did the strings live on I Need You to Tum To and, I think, The King Must Die. (That is one of my favorite Elton songs I’ve worked on because of the mysterious lyric and the humorous quality of the track.) Elton was screened off and the rhythm section was boothed off from the rest of the musicians in the studio, which would have been a string section or brass section. Or woodwinds.

“And even though that was just a 20-piece string section (as opposed to upwards of an 80-piece full orchestra) – like a small chamber orchestra, really – it was written in a kind of symphonic way.

“Take Me To The Pilot has only cellos in the orchestral part, although at the climaxes they play towards the high-end of their range. I asked for the cellos to be phased on that song. And since nobody objected to it – on the contrary, they supported the idea – we went ahead and did it.”

Paul not only wrote the orchestral parts for eight of the 10 songs on the Elton John LP, but he also arranged the entire album (save one song) as well as its singles’ B-sides Grey Seal and Bad Side Of The Moon. Paul created charts for nearly every musician; nearly everything you hear on that album that isn’t Elton is a result of Paul putting pen to paper.

“For example, in the case of the drum parts, I’d write all the fills, or the first of any typical kind of fill, which would give the drummer the idea of what I was looking for. So, for instance, I would write the first pick-up into a two-bar phrase. Then, for the subsequent two-bar phrases, I would just indicate, ‘repeat.’ That is how a groove was established. Also, I would include details such as open hats (hi-hats) or half-open hats. As the song developed and it built and we wanted a full snare, that would be indicated.

“Of course, the drummer was chosen because he had a certain feel and he would bring his own particular interpretation to the part. There would be a certain amount of latitude between the rhythm section players to play off of each other, and to play off Elton. On pieces like No Shoestrings On Louise, all I did was give them the chords and they just played as a band, which was right for that song. And I actually didn’t have much, if anything, to do with the vocal harmonies. Percussion was generally not written, except for the entries, because those were more like decorative things and didn’t need to be worked out. But everything else was completely written.

“Generally the song itself will dictate to me what I have to write. If I’m listening and paying attention to the song it makes itself clear to me in a very short time. It’s a little bit like that thing Michelangelo said: ‘There’s a block of stone and the sculpture is hidden inside of it.’ Actually, it’s even easier than that; the song is already sculpted – it’s prepared. The song is already written and the character of what I had to write is inherent in what I heard. So I’m bringing up certain characteristics that are already there, even if not in fully-expressed form.”

The György Ligeti-inspired buzzing string section at the beginning of Sixty Years On, which Paul was often complimented on, was in fact recorded separately from any song and stuck on by Gus.

“There was some downtime in the studio during a string session. Having finished early meant that we had time on our hands to do anything we like with the string section because they were being paid to be there. So, just out of a sense were of fun I dictated a set of notes to the string section, which they wrote down. Very simple – maybe one or two notes to each group of three or four players. We had 21 strings on that date. I proceeded to conduct them after having told [engineer] Robin Cable to start recording. This was off the top of my head; there was nothing planned about this. The first entry was, say, a viola note. Two of the violas started with the first note. And as I wasn’t conducting to a beat, I would then point to the next two violas that came in with the next note. Then two of the second violins would come in with the next note. And so on until the whole section had joined in. I had also indicated where I wanted certain kinds of vibrato (wide or narrow), which helped to create that effect. So we recorded that…and there it lay. And Gus went on to add that to the front of Sixty Years On. I hadn’t conceived the arrangement that way.”

Paul did, however, come up with the idea of having a harp begin the song, feeling that it would mix things up a bit to transcribe Elton’s piano demo intro for fellow Royal Academy alumnae Skalia Kanga. And it is Paul himself playing cello at the beginning of The Greatest Discovery.

‘Tumbleweed Connection’

“It was not recorded all at once. We weren’t always available at the same time. Gus may have been on other projects. Elton was probably touring. Maybe studios weren’t available. The vibe was different because we weren’t all concentrated into that 12-day period that the Elton John album was recorded and mixed in. It was spread out more.

“On Tumbleweed Connection, there was this whole old-western feel. The sound of the album is sepia-tinted, like the cover art. When I think of those songs, that is what I see visually. You think of old western steam trains and you think of clanking wheels on the rails. Hard-bitten creased faces of cowboys with squinty eyes looking off in the distance. You can almost smell the old leather. That’s the feel of the album. It’s very authentic. It’s a tribute to the old American West.

“Come Down In Time and Burn Down The Mission were the only two total arrangements I did on that album. I have a vague memory that Come Down in Time was finished and recorded – without my involvement – and I asked Gus to have me re-do it. ”

Elton’s live performances at the Troubadour – interpreting the orchestrated ‘Elton John’ album with a three-piece band

“Elton’s way of playing the piano was really full. So that’s one factor that made for a very rich sound for a three-piece. Dee’s wonderful…not merely playing the bass part but making that part of the bigger picture. Nigel’s very warm and full drum sound and vocals. It was more than a three-piece. It’s greater than the sum of the added parts and they managed to make a sound that was very full. Fans and music-goers at the concerts didn’t notice a lack of orchestra or anything like that. And that’s great because one of the things that I was concerned about at the time was, ‘How is Elton going to take this [Elton John album] sound on the road with a small group?’ And he did – it worked beautifully.”

‘Friends’

“Elton was hired to write three songs as principle score (Friends, Michelle’s Song and Seasons) and two songs as source (Can I Put You On and Honey Roll). ‘Source’ means coming from a radio or television, or it can be a band in a nightclub. [Something on screen in the film.] I did not arrange the two source songs but I played conga, would you believe, on Can I Put You On.

“At the time I was very pleased with what I did. Subsequently, you start to look at things more critically, I suppose. Time goes by and you can see what you’ve done. At the time it was a strange experience. It was my first dip in the pool…more like thrown in the deep end, sink or swim. And I managed to swim well enough.”

This is a song with a revolutionary string arrangement. For songs like this, when we recorded it, nobody did string arrangements like this and this is why Buckmaster was so good.

‘Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player’

“That session [Have Mercy On The Criminal] was an over-dub to a pre-existing track. I was given a finished track to write a string arrangement to go over the top of it. There’s this electric guitar phrase, which starts the song off, which is what I doubled. So I don’t know if what I did was such a big deal.”

‘Made In England’

“I think Believe has one of the most powerful lyrics. It is a very gripping song. An exciting, dramatic song. If you’re willing to be taken on a trip like that then it’s quite a powerful experience. Sometimes I’m not quite sure what [Bernie] means in his lyrics – I think he allows that to be a part of his style – but I’ve always loved what he’s written. There’s such a powerful imagery in his lyrics, and in what results from Elton turning them into songs. A new cycle is beginning for Elton, I think, with this album.

“I composed two weird intros to House [and one was chosen for the album]. [Producer] Greg [Penny] and Elton said, ‘Why don’t you write something that recalls a little bit the intro to Sixty Years On?’ In this instance at least, I did what should have been done with Sixty Years On – compose it deliberately.

“Elton asked me to compose a prelude to Belfast. I think [he felt] that, while you could just start it with [Elton’s part of] the start of the song, and that would be fine, in a way the song gains something special by having this piece in front of it. The prelude starts with the same theme that I used in the coda of Believe. And there are chord-sequence quotes and references to Belfast in the prelude. It ties everything together. On the song’s last chord, I held it for a very long time. I had the violas and the second violins oscillating between two notes. But you have to really stretch your ears to listen to it because it was intended not to be heard. It was intended to be a textural effect, but if you pay careful attention you can hear this rocking oscillation.”

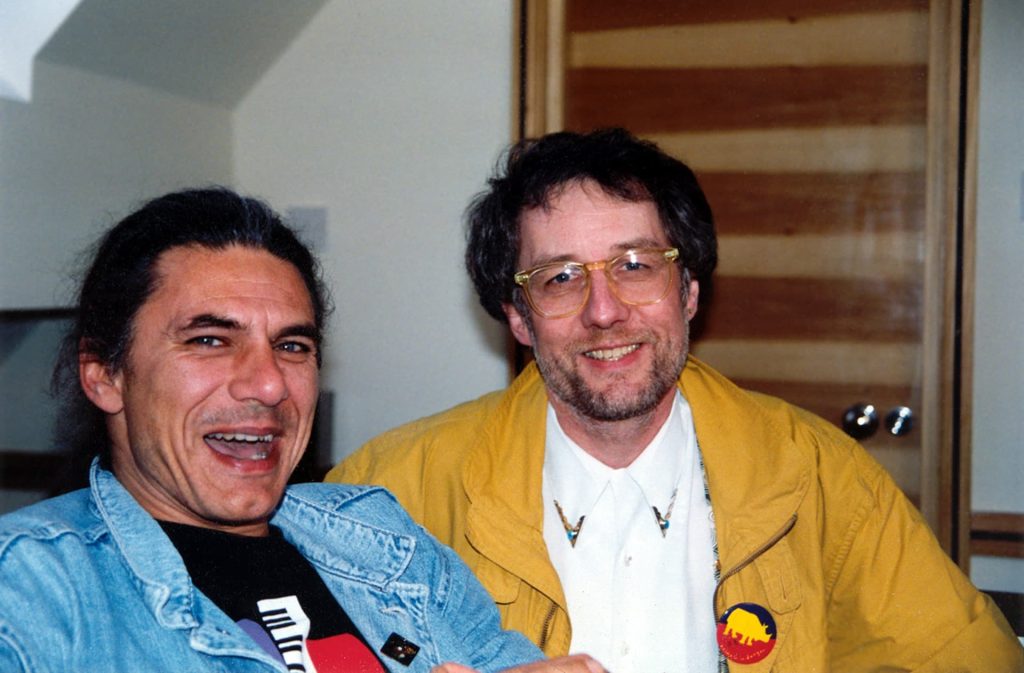

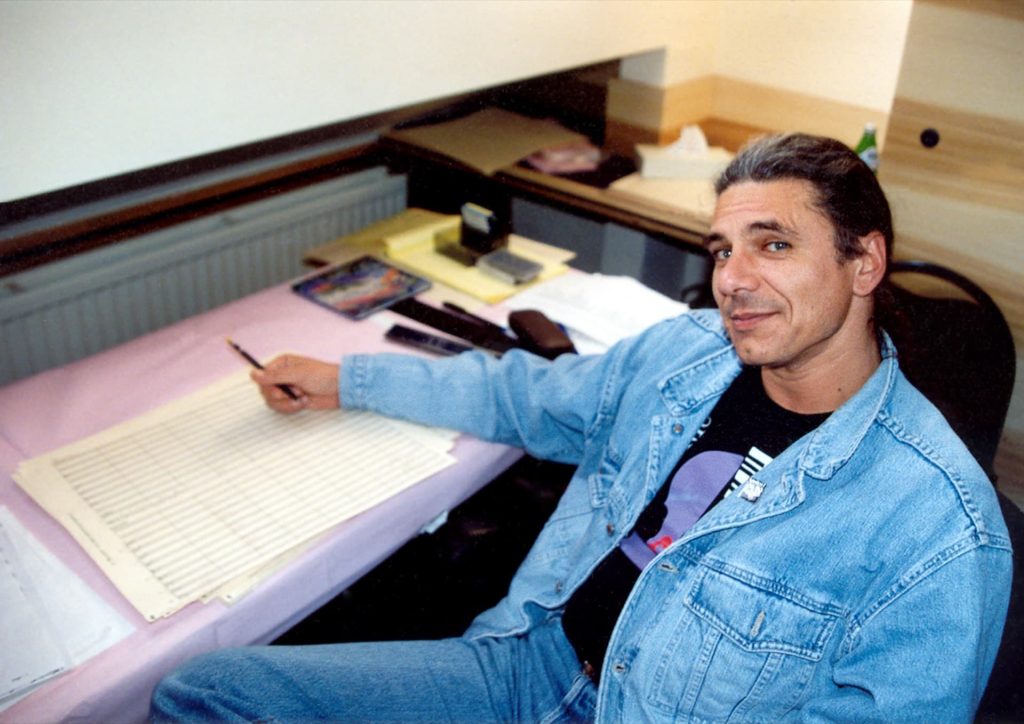

Paul Buckmaster at AIR Lyndhurst Studios during the 'Made In England' sessions. (Photo: John F. Higgins)

“I really like what I did on Cold. It is a kind of mid-tempo thing, but it gets quite up there in terms of intensity. At the same time, what I’ve done with the orchestra I think complements the song very well. There is some stuff I did on [Made In England] that I had not done before on any kind of pop recording, certain ways of harmonizing. I really went far out with certain harmonizations on Cold that I would not have thought of doing in an earlier era.”

“I saw Elton in concert some time after we finished Made In England and he started playing this long intro and I didn’t know what it was and little by little it started teasing my memory. I realized after it must have been eight minutes (it seemed to go on for a long time but was not at all boring…very interesting, full of surprises) that it had elements of Take Me To The Pilot in it.

“And in fact, it was an extended intro to Take Me To The Pilot, and he displayed such humorously brilliant inventiveness on that piano intro and I was just knocked out. It means that he’s very interested in developing his musical abilities.”

Paul’s work with Elton:

★ Elton John (1970)

- Full arranger on 10 songs + 2 b-sides

- Orchestral arranger on 8 songs + 1 b-side

- Cellist on 1 song

★ Tumbleweed Connection (1970)

- Full arranger on 2 songs

- Orchestral arranger on 3 songs

- Horn arranger on 2 songs

★ Madman Across The Water (1971)

- Orchestral arranger on 5 songs + 1 b-side

★ Friends (1971)

- Composer on 4 songs

- Orchestral arranger on 8 songs

- Congas on 1 song

★ Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player (1973)

- Orchestral arranger on 2 songs + 1 b-side

★ Blue Moves (1976)

- Orchestral arranger on 2 songs

★ A Single Man (1978)

- Orchestral arranger on 6 songs + 3 b-sides

- ARP synthesizer on 1 song

★ Made In England (1995)

- Orchestral arranger on 4 songs

★ Songs From The West Coast (2001)

- Orchestral arranger on 4 songs

- Horn arranger on 1 song