Menu

‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’ – Recording

Originally, the location selected for recording Elton’s seventh album was Dynamic Sound Studio in Kingston, Jamaica. The Rolling Stones had recently recorded Goats Head Soup there, and the facility looked very appealing to Elton and producer Gus Dudgeon for a variety of reasons.

“In Jamaica I hope to be cut off and uninterrupted,” Elton said in an interview with NME’s Danny Holloway in early 1973. “Gus went to have a look at the studio and spoke to Charlie Watts, and he says it’s really conducive to hard work. … [Studio owner Byron Lee] said we’d have to go there to really appreciate the feel.”

Producer Gus Dudgeon at the Château d Hérouville. (Photo: Greg Penny)

Truer words were never spoken, but perhaps not in the way they were intended. Elton, lyricist Bernie Taupin, Gus, engineer Ken Scott and the band (guitarist Davey Johnstone, bassist Dee Murray and drummer Nigel Olsson) arrived in Jamaica in late January 1973 and were witness to a city in the throes of hosting the Joe Frazier vs. George Foreman heavyweight boxing championship fight. Imagine Times Square on New Year’s Eve…over a week or so.

In addition, owing to some socio-political struggles that were going on at and around the studio at the time, the working atmosphere was less than conducive to creativity. In Ken Scott’s book, Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust, he describes the tension, “On our first trip to the studio, these lines of [Dynamic Sound] workers began rocking our mini-bus with the intent of trying to push it over. It was very hairy for a bit and we were all terrified, and almost cancelled the session then and there.”

Once they got inside the studio, things were not much better; the recording team found they were utterly unable to get a decent sound mix owing to a dearth of microphones and a recording system that was not up to the standard with which they had become accustomed. As Davey Johnstone says, “We did a version of Saturday Night’s (Alright For Fighting) that sounded like a bunch of angry bees. It sounded terrible.” After a day or two of attempting to overcome the setbacks the decision was made to abort the sessions entirely and try again elsewhere later on. In the meantime, Elton had written a number of songs at his hotel in Kingston.

Elton recording the lead vocals to Candle In The Wind. (Photos: Greg Penny)

Four months later, the team (now with engineer David Hentschel behind the board) reconvened at the Château d’Hérouville in France: an 18th century structure 30 miles from Paris where Elton had recorded his previous two records. Working on an album they thought would be named Silent Movies And Talking Pictures because of the many cinematic themes of the lyrics and songs, they began on May 7 by tracking the three songs that would become side one of the album on the studio’s MCI 416 console and 16-track Ampex tape machine. Elton and the band then spent the next two weeks working on the rest of the songs originally written in Jamaica, plus a number of additional tunes that he and Bernie were writing as the sessions progressed. As Hentschel explains, “There was a big room where we’d all have breakfast. Bernie had brought the lyrics down – there was a piano in the eating room – and I remember Elton sitting down and writing. I was watching him doing it as we were eating breakfast (and then we all went in and recorded it) and I’m pretty damn sure it was Candle In The Wind.”

It soon became apparent that they had more than enough material for a single album. “We probably would never have made a double album if it wasn’t for the fact that we went to Jamaica and Elton was in a roaring mood,” Dudgeon said in a 1993 interview. “He just wrote song after song after song. Then when we went to France he was so used to sitting down at the piano and writing songs before sessions began that he wrote some more. Suddenly, we had two albums’ worth.” Indeed they did; the full album consists of 17 songs containing 76 minutes of music (86 minutes if you include the 3 non-LP b-sides to the album’s singles).

Once the basic tracks, guitar overdubs, and lead and background vocals had been recorded at the Château, it was up to Gus and David to put on the finishing touches and mix the album. This took place at Trident Studios in London (the site of Elton’s album sessions prior to France). Percussionist Ray Cooper was brought in to play tambourine on All The Girls Love Alice and arranger Del Newman (who had worked with Elton when he was still Reg Dwight on some demo sessions in 1968) did orchestral arrangements on six of the songs.

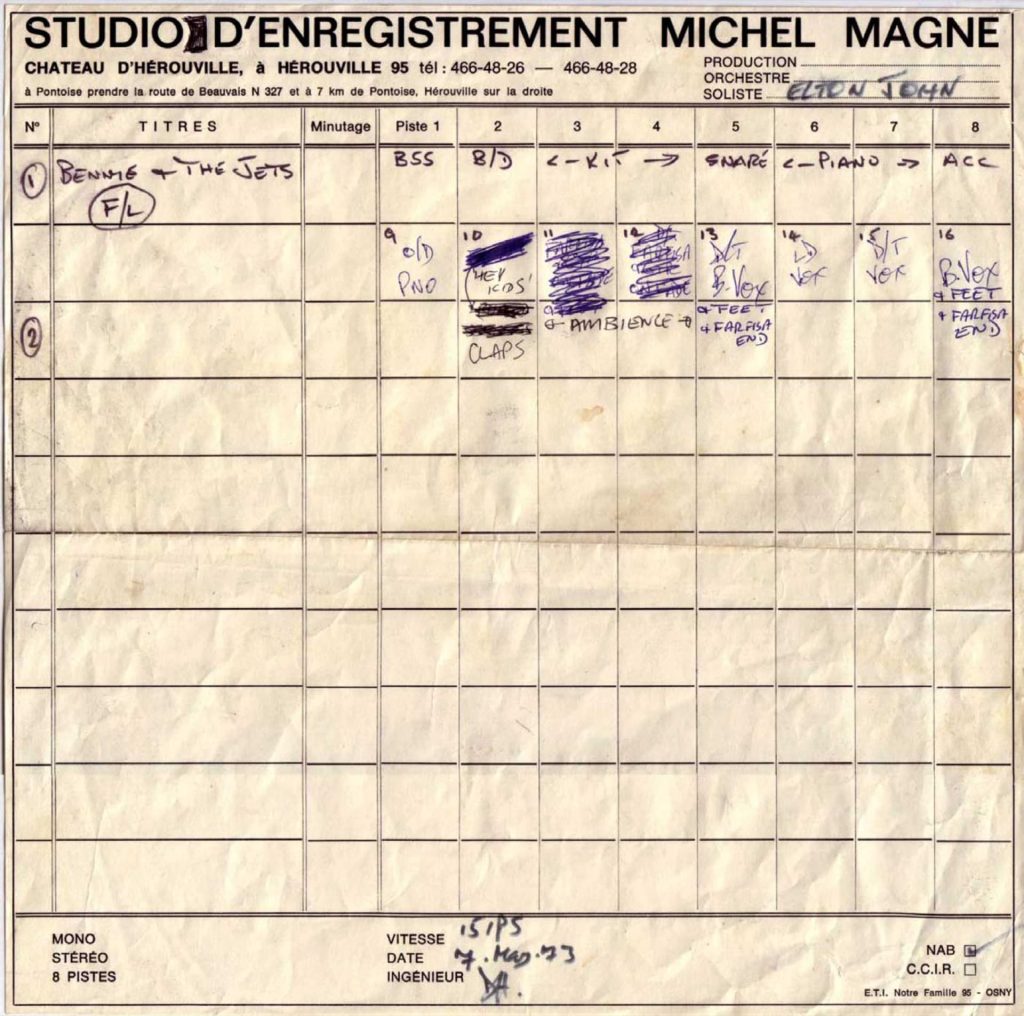

Original studio track sheet for Bennie And The Jets.

It was at Trident that Bennie And The Jets transformed from a studio track to a “live” one. As Gus explained, “I was doing the mix and for some weird reason, Elton happened to have hit the opening piano chord of the song exactly one bar before the song actually started. [I thought], ‘It’s the sort of thing that people do on stage just before they’re going to start a song.’ For some reason that chord being there made me think, ‘Maybe we should fake-live this.’ So we did. The whistling is me and some other guys and the applause is taken from when Elton did the Festival Hall, plus a bit of Jimi Hendrix’ Live at the Isle Of Wight.”

Also recorded during the overdub sessions was the beginning of the album. The first minute and 40 seconds of Funeral For A Friend is an overture Hentschel arranged and performed on an ARP synthesizer using themes from songs within the album. Keen listeners may be able to identify variations on melodies from I’ve Seen That Movie Too, The Ballad Of Danny Bailey, Candle In The Wind, and others in the eerie intro. Watch our exclusive Funeral For A Friend “Melody Guide” video here.